Many molecular systems are highly heterogeneous yet functional: for example, natural photosynthetic systems (e.g., green plants) are messy and noisy on the microscopic scale, but harvest sunlight at efficiencies much higher than any man-made solar cell. Understanding the principles of molecular organization in complex systems to achieve their functions is critical to the design and improvement of new materials. Due to the complexity of these systems, their microscopic structures are difficult to probe in experiment, and in many cases, experimental data are interpreted with the aid of theory and modeling. We are interested in developing and applying simulation models to understand these systems, such as organic/hybrid semicondutor devices, and proteins at surfaces. Whenever possible, we like to validate our models against experimental data, in particular vibrational spectroscopy.

How do we simulate these systems?

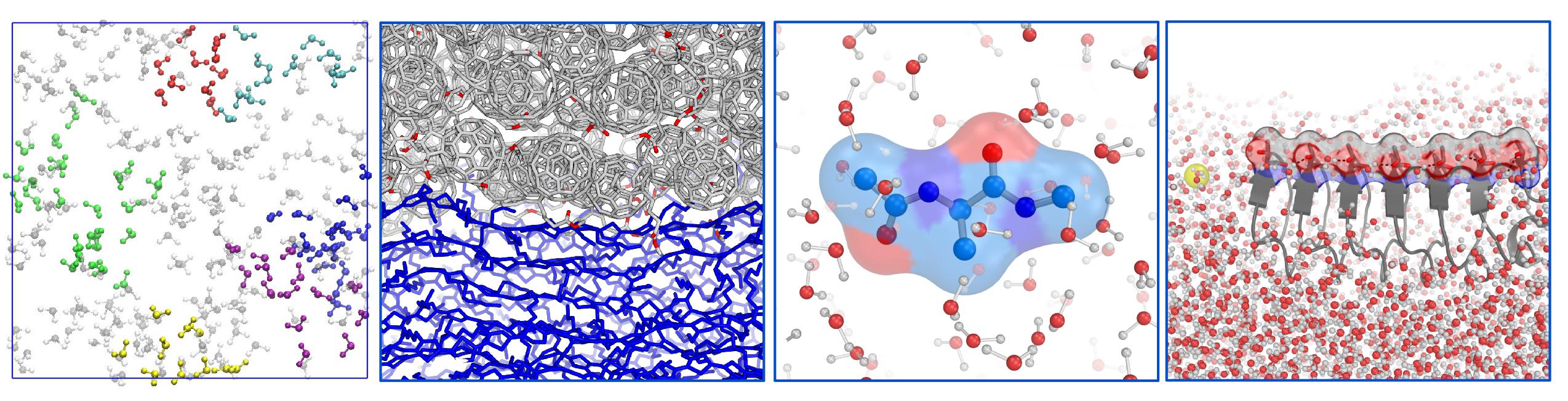

We mostly perform classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (some MD snapshots of our simulated systems are shown above), but whenever needed, we use quantum chemistry to guide the use of force fields. We then compute various structural and dynamical properties, including spectroscopy, and validate our simulation by comparing the calculated properties with experiment.

Why do we model vibrational spectroscopy?

Molecular vibrational spectroscopy is particularly useful in reporting local molecular structures of complex systems, ranging from biological aqueous systems to amorphous solid materials. However, other factors such as thermal broadening also contribute substantially to the final spectra, and their interpretations are sometimes challenging, in particular for the state-of-the-art ultrafast spectroscopy (e.g., 2D-IR). Spectroscopic modeling is proved to be invaluable in dissecting experimental spectra, and more importantly connecting them directly to microscopic molecular configurations.

How do we model vibrational spectroscopy?

It depends, but our calculations are all based on some time correlation functions (TCFs). Sometimes we are lucky, and we can just compute classical TCFs directly from MD simulations. Sometimes we need to add some flavor of quantum mechanics into our model, namely using some mixed quantum/classical approaches. Very often, we like to write our own codes to do spectral simulations.

…and what matters?

We believe that simulation matters when it connects to experiment so that simulation can help experimentalists interpret and possibly design their experiment, and experiment can help theorists refine their simulation models. Once the simulation model is trustworthy, it is our hope that simulations can guide experiment to improve the functionalities of these complex systems.